Deaf Awareness Month

Dr. Rebecca Blaha, lead audiologist at the Pennsylvania Ear Institute (PEI) and assistant professor at the Salus University Osborne College of Audiology (OCA), discusses celebrating September as Deaf Awareness Month with guest Dr. Kathleen Riley.

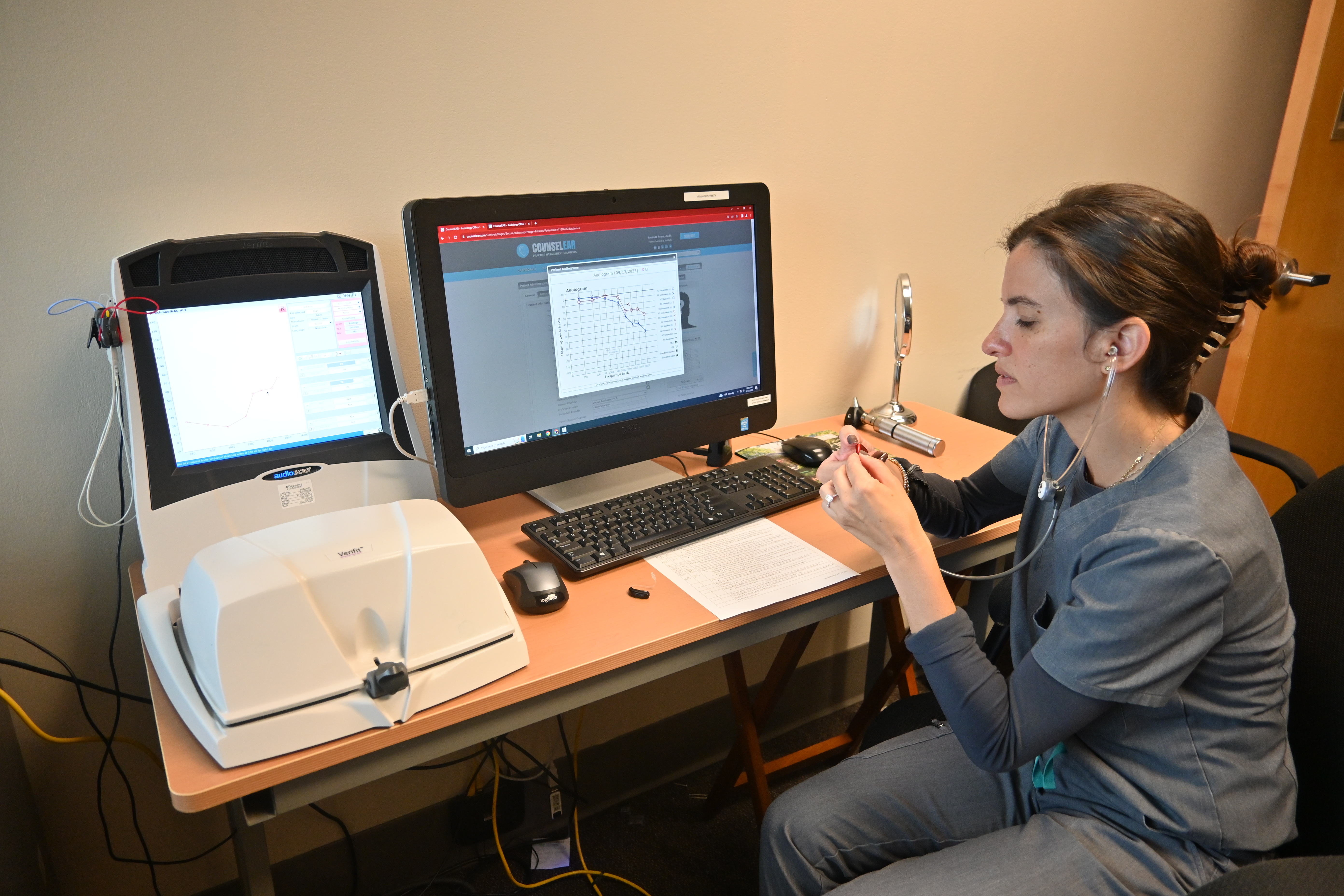

Blaha: I've been an audiologist for the past 18 years, and I'm currently an assistant professor at OCA at Salus University. I'm also the lead audiologist at PEI, the on-campus training facility for our students. Attending the four year doctor of audiology program, I specialize in all things amplification from traditional hearing aids and assistive devices, as well as cochlear implants and bone conduction devices. Additionally, I provide services related to tinnitus management. I'm joined today by Dr. Kathleen Riley, who is an educational audiologist. Kathy has worked with and for deaf and hard of hearing adults and children for 40 years.

She's also the vice president of advocacy for the Educational Audiology Association. Kathy also teaches an educational audiology course here at Salus as well as oral rehabilitation classes for speech-language pathologists. The purpose of the PEI podcast is to be educational, and I'm excited for today's topic. We are here to celebrate September as deaf awareness month. In doing research for this topic, I learned that the celebration originated in 1958, so it's been around a lot longer than I realized as International Day of the Deaf and has since grown into a month-long celebration. But what I think is even more important is to recognize that deafness, and I'm spelling that with a lowercase d, encompasses many different aspects of hearing, not just to recognize individuals that identify with deaf culture spelled with a capital D. I'd like to get your perspective having worked with people across all levels of hearing in your career.

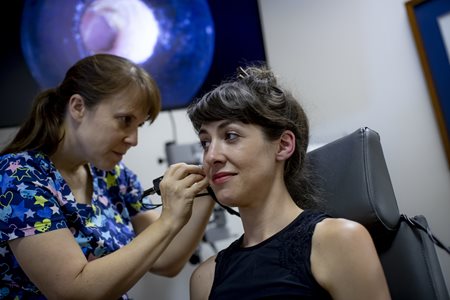

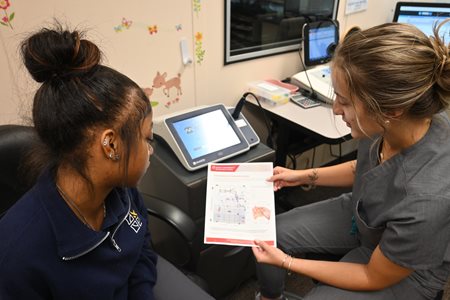

The Pennsylvania Ear Institute offers a variety of services including comprehensive hearing evaluations, hearing aid fitting and repair. For more information on PEI’s hearing aid services, call 215.780.3180.

There are many hard of hearing persons who are part of the deaf community. There are also some hearing people who are either fully or partially within the deaf community, such as hearing children of deaf adults for whom ASL was perhaps their first language. ASL interpreters are often included. I have to be honest, very few audiologists are considered to be part of that community or accepted within that community. And there's a really good reason for that. And it's related to the topics of what we call audism, which is similar to racism or sexism.

A lot of people also use the term ableism. It's the idea that because someone has less than typical hearing that they are in some way inferior and need to be fixed. It is true that within our profession, many members are highly focused on solving hearing differences and helping deaf people to somewhat pass as hearing people and don't, we're not always careful about taking into consideration their own self-determination. I often am highly involved in the deaf community, but typically, when I meet new deaf people, I don't tell them that I'm an audiologist until they specifically ask because we are not viewed very favorably, unfortunately. And most deaf people are amazed at my level of fluency in ASL because that is rare in our profession. But I want to be fair because that culturally deaf Big D population is really a very small percentage of the people that we serve as audiologists.

A lot of people also use the term ableism. It's the idea that because someone has less than typical hearing that they are in some way inferior and need to be fixed. It is true that within our profession, many members are highly focused on solving hearing differences and helping deaf people to somewhat pass as hearing people and don't, we're not always careful about taking into consideration their own self-determination. I often am highly involved in the deaf community, but typically, when I meet new deaf people, I don't tell them that I'm an audiologist until they specifically ask because we are not viewed very favorably, unfortunately. And most deaf people are amazed at my level of fluency in ASL because that is rare in our profession. But I want to be fair because that culturally deaf Big D population is really a very small percentage of the people that we serve as audiologists.Blaha: I can think of only two patients currently that see me for audiology services. And I don't think either one of them identifies as culturally deaf, although I do provide them with interpreter services when they come in for the appointment, they are wearing amplification. But it is more for sound awareness, it's more in a limited capacity.

In looking up resources for today's discussion, I thought it was interesting that some people would not say that they have hearing loss because if they were born without that, they don't feel that it has been lost. In their instance, deafness was not disabling because it was how they learned. It's an interesting way that we have to consider self-identity because as you mentioned, there's a lot of people that might have usable hearing as we would say amplification could be beneficial. And they do still identify within deaf culture, which I think I would need to know more about. In terms of the culture, is it strictly just the language or are there other traditions and things that define it?

Blaha: During my research and looking into some articles that discussed how you basically celebrate September as deaf awareness month, one of the interesting comments was asking someone, what form of communication do you use or what form do you prefer? And that's not something that I have encountered because from my perspective, I've always worked with older adults and they're coming in for the use of amplification. In that instance, they communicate through spoken and oral communication. I don't have to be concerned with whether or not they want to use an alternative form and maybe want to learn sign language and things along those lines. But during my training when I was doing my master's, we had to talk about how you need to offer total communication to families when they are looking at newly diagnosed children and things like that. You have to offer them every option that's available. And I think that's interesting how it's very different between the populations.

But I think we forget that it's not just about the ear, it's also about the central auditory nervous system and how the brain is able to process hearing what I hear many times. I've worked in deaf education and educational audiology for years. Kids will say things to me, I just can't hear fast enough. I think that many times communication situations or classroom situations are not set up well for children. So yes, we do talk about total communication that really is a term that's fallen out of favor somewhat in that it originally was meant to be anything that worked to get the message across, and there was like 13 criteria, but it very quickly became what we now call simultaneous communication, which is using English word order and supporting that English word order with signs. Unfortunately, ASL does not work in the same grammar that English does, so one of the languages has to give up.

But I think we forget that it's not just about the ear, it's also about the central auditory nervous system and how the brain is able to process hearing what I hear many times. I've worked in deaf education and educational audiology for years. Kids will say things to me, I just can't hear fast enough. I think that many times communication situations or classroom situations are not set up well for children. So yes, we do talk about total communication that really is a term that's fallen out of favor somewhat in that it originally was meant to be anything that worked to get the message across, and there was like 13 criteria, but it very quickly became what we now call simultaneous communication, which is using English word order and supporting that English word order with signs. Unfortunately, ASL does not work in the same grammar that English does, so one of the languages has to give up.Usually ASL has to give up most of its salient features. There are people who have learned that way and use that, but the more common approach now is what we call bilingual education where you're using both English and ASL, but you're not using them at the same time and you're using them alternatively. If I am working with a family and the parents don't sign well, which is sadly very common, I might talk to that student in ASL and then turn around and repeat myself in English to the parent or speak to the parent and then turn and repeat myself in ASL because when I mix the two languages, I mix the grammars and that makes both, neither language is now correct. Language acquisition becomes a very, very complicated process. And I think that if we respect our parents and our families and our children with hearing differences, then we're going to do data-based collection.

We're going to make decisions based on evidence and not on bias and not on tradition. Unfortunately, many audiologists don't get a lot of training on that. And so that's part of the class that I teach is how do we gather that relevant information to help make evidence-based decisions for children with hearing differences who are typical learners and do not have other disabilities. We should be expecting one year's growth in one year's time just like every other child. And any excuses that that's not happening means that the formula we've set up is incorrect, whatever that is. Perhaps there's things that are supposed to be happening at home that are not, that we need to really work with the family on. It might be how the classroom is set up. It might be the ability of that child to quickly and accurately process spoken English. So I think we need to go back and look at the formula and look at what's missing or what needs to change and allocate different resources to allow that child to make a year's progress in a year's time.

We're going to make decisions based on evidence and not on bias and not on tradition. Unfortunately, many audiologists don't get a lot of training on that. And so that's part of the class that I teach is how do we gather that relevant information to help make evidence-based decisions for children with hearing differences who are typical learners and do not have other disabilities. We should be expecting one year's growth in one year's time just like every other child. And any excuses that that's not happening means that the formula we've set up is incorrect, whatever that is. Perhaps there's things that are supposed to be happening at home that are not, that we need to really work with the family on. It might be how the classroom is set up. It might be the ability of that child to quickly and accurately process spoken English. So I think we need to go back and look at the formula and look at what's missing or what needs to change and allocate different resources to allow that child to make a year's progress in a year's time.

Riley: It's interesting you say that because I've been supporting a young woman who has early adult onset hearing loss that began at the very end of high school and she's now in graduate school and really did not know anything about her legal rights or the technologies and the supports that are out there. She didn't really know about automatic speech recognition, the captioning systems that we use. She didn't know how to get those services at the college level. I've worked with people of all ages, and it's a very prevalent idea in our society that hearing is an undesirable trait that hearing loss is an undesirable trait.

So getting people to say to someone, let's say you're at the drugstore saying to the person, I'm sorry, I don't hear well, or I'm hard of hearing, can you look at me when you talk? Or can you slow down? I talk a lot in my classes about teaching repair strategies. Not just saying what, but saying, okay, my appointment is on Wednesday at what time? I repeat back the part that I understood and ask for clarification on the part. I do not. I wonder sometimes for older people with age-related hearing differences, if they know enough about things like CapTel or clear caption. The phone system has just a little screen, it comes up in print, you speak for yourself, but then you can double check through print that what you thought you heard is indeed what you heard. I think that some of, as an older audiologist, I feel like some of the intervention that was really taught when I was in school has gone by the wayside. Technology medicine has just taken off at light speed. And so I think we get very caught up in assessments and provision of technologies, but I'm not sure that we do enough as an interventionist to help people solve their day-to-day living problems.

So getting people to say to someone, let's say you're at the drugstore saying to the person, I'm sorry, I don't hear well, or I'm hard of hearing, can you look at me when you talk? Or can you slow down? I talk a lot in my classes about teaching repair strategies. Not just saying what, but saying, okay, my appointment is on Wednesday at what time? I repeat back the part that I understood and ask for clarification on the part. I do not. I wonder sometimes for older people with age-related hearing differences, if they know enough about things like CapTel or clear caption. The phone system has just a little screen, it comes up in print, you speak for yourself, but then you can double check through print that what you thought you heard is indeed what you heard. I think that some of, as an older audiologist, I feel like some of the intervention that was really taught when I was in school has gone by the wayside. Technology medicine has just taken off at light speed. And so I think we get very caught up in assessments and provision of technologies, but I'm not sure that we do enough as an interventionist to help people solve their day-to-day living problems.For instance, when I'm looking at, I think for all patients, all patients, but especially for children, because that's what I focus on, speech and noise testing is mandatory as part of your standard evaluation. No one hears in a sound treated booth where it's completely quiet with nothing to look at. At the minimum, I want children to have speech and noise testing at 55 dB and then at 35 dB so that we are looking at close speech and then speech that's further away. And I want it in a variety of signal to noise ratios because that helps inform us do they need to use a remote microphone? Do they need some text support? They have many adults with hearing challenges who have Otter.ai voice recognition software on their phones. So when they go somewhere including the doctor, they turn that on, and again, they have some print support to what they think they're hearing.

I especially worry about the healthcare system because most of our doctors are not trained to deal with big D or small d people who hear differently so that they turn their back and they're washing their hands while they're talking to the patient or whatever those things are. I know for my parents, one of us always goes to a doctor appointment with them anymore because they can't understand the doctor, and especially if the doctor is not US-born, but also because even if they are native spoken English users, sometimes the terminology and the concepts are very difficult. And I'm not sure that we train our medical providers to think about those issues with our patients. Any of our patients.

I especially worry about the healthcare system because most of our doctors are not trained to deal with big D or small d people who hear differently so that they turn their back and they're washing their hands while they're talking to the patient or whatever those things are. I know for my parents, one of us always goes to a doctor appointment with them anymore because they can't understand the doctor, and especially if the doctor is not US-born, but also because even if they are native spoken English users, sometimes the terminology and the concepts are very difficult. And I'm not sure that we train our medical providers to think about those issues with our patients. Any of our patients.

Riley: I think that we need to be acutely aware of that, not only with adults, but also with children. How do children learn health literacy if we're always talking to the parents? So as an educational audiologist, I partner with clinical audiologists, and I would have students who came back the next day, and I knew they'd been at the clinical audiologist, and I say, “so what happened? What did you guys decide?” And they just look at me. They go, I don't know. My mom knows because no one was talking to that child. I really encourage all audiologists working in pediatrics to talk to the child and allow the parent to listen. The parent can then ask more complicated questions or additional questions if they need to, but the child is your patient and your allegiance should be to that patient. And children cannot learn about their own bodies and their own health if we are not providing that information in a helpful way. So it's one of the things that I talk a lot about with pediatric audiologists.

Blaha: I remember that distinctly in graduate school, now we're talking 20 years ago, but they said, even when the patient needs to use interpreter services, don't let yourself be distracted by the interpreter because the patient is still sitting next to you, even though you're interacting with that interpreter. They're not the one that you need to truly impart the information to. And that can be distracting to realize, okay, the interpreter's here, but my patient is seated over here. And to always make eye contact and be respectful, that person.

Blaha: I remember that distinctly in graduate school, now we're talking 20 years ago, but they said, even when the patient needs to use interpreter services, don't let yourself be distracted by the interpreter because the patient is still sitting next to you, even though you're interacting with that interpreter. They're not the one that you need to truly impart the information to. And that can be distracting to realize, okay, the interpreter's here, but my patient is seated over here. And to always make eye contact and be respectful, that person. Riley: You always speak to the deaf person or your patient and they will look at you. They'll look at the interpreter while you're talking. Then they will look at you while they answer. So they're also making eye contact with you. It is very dismissive to look at the interpreter or talk to the interpreter or say to the interpreter, I just was with a group of deaf friends yesterday, and this conversation came up that the doctor will say, or whoever will say to the interpreter, tell them I said this. Tell them I said that as if they're a third party rather than the patient. I do think, and again, norms change over time. Even using the word, I never use the word hearing impairment. It is rampant in our research and our literature, but to me that is, again, a very honest or ableist term in that it suggests that that person is a broken form of the hearing person they were meant to be, rather than a person who hears differently.

I'm actually working on a document with some deaf audiologists for the Educational Audiology Association (EAA) about preferred or acceptable terminology and saying things like hearing differences, reduced hearing, atypical hearing. As you said, when you grow up with hearing loss, whether you're born with it or it happens early in life, it doesn't feel like a loss. It is just a normal experience for adults who are normal hearing people and they have experienced hearing changes. Yes, those people might consider that a loss. But even in the new American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) document, they talk about sensory neural hearing change. They do not use the word loss. So it'll be interesting to see how things change over time with new social norms.

I'm actually working on a document with some deaf audiologists for the Educational Audiology Association (EAA) about preferred or acceptable terminology and saying things like hearing differences, reduced hearing, atypical hearing. As you said, when you grow up with hearing loss, whether you're born with it or it happens early in life, it doesn't feel like a loss. It is just a normal experience for adults who are normal hearing people and they have experienced hearing changes. Yes, those people might consider that a loss. But even in the new American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) document, they talk about sensory neural hearing change. They do not use the word loss. So it'll be interesting to see how things change over time with new social norms.

Riley: Especially when you're working with newborns or young children, when we as the professionals sit down and say, with pity in our voice, I'm so sorry to tell you, but your child has hearing loss. We have already set that family up to assume that it's an undesirable event. And I often say to families, I've worked in early intervention for a long time, and I say to families, This is a different journey than you envisioned, but I promise you there will be many grand adventures along the way. So I also, in talking with teens and young adults, I tend to objectify hearing loss. So I say things like, your ears don't allow you, or your hearing doesn't allow you to understand someone talking when their back is hurt, or I don't say, you can't do this.

I say, your hearing loss or your current hearing levels or your current technology does not allow you to do this. How else are we going to manage this situation? And we talk a lot about other workarounds for that situation. And I think that that does help because I've had students say to me, everyone says, I'm smart, but I was never smart enough to learn to hear. And so somewhere along the way, they missed the idea that it was not about their intelligence, but it was a biological transmission issue that has always broken my heart. So I kind of have changed how I talk about things in order to make sure that that child understands that they are whole and perfect. They just don't hear the same as everyone else.